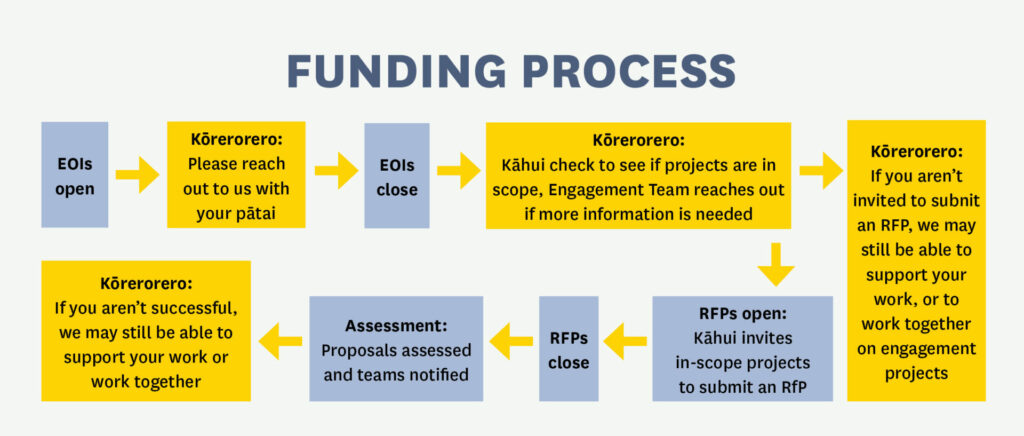

Do we have to partner with a mainstream institution to apply for Te Taura?

No! Not at all. It may be more likely that Te Taura applications involve relationships or collaborations with either universities or CRIs. However, it’s by no means a criteria for Te Taura applications. We want to encourage research collaborations that are meaningful and that support kaupapa Māori research and the vision you have for your rangahau.

Can we apply for both Te Aho and Te Taura? Can we submit multiple EoIs?

Yes, we’re happy for you to submit multiple EoIs. And yes, we’re happy for you to apply to both research funds. In both cases, please take the process seriously and think carefully about your kaupapa, your capacity and your research goals. Please submit your best applications, so we get a real sense of your priorities and your readiness to undertake research. We also strongly encourage members of the same iwi to work together. Multiple applications from members of the same iwi on the same kaupapa will be difficult for us to assess.

Can Councils apply for this funding, in partnership with iwi?

Strictly speaking, no. This funding is for kaupapa Māori research that is by Māori and for the benefit of Māori communities. However, if iwi want to pursue research that involves or requires Council input (such as research, engagement, data provision, etc.), these kinds of projects are definitely “in-scope”. We would hope that Councils provide in-kind funding, for example through staff resource. We won’t fund roles or contributions to projects where these are already funded as part of the everyday business of Councils.

How will the total pool of funding be allocated? Will it be equitably shared across the motu?

The Challenge’s final decisions will depend on the range and nature of all the project ideas that are submitted. We have limited funding. We may choose to fund across different geographic areas. Or, if there is a strong case that research in only a few rohe is likely to bring significant benefits nationally, we might invest in only a few geographic areas. Regardless, we encourage you to submit your best research ideas.

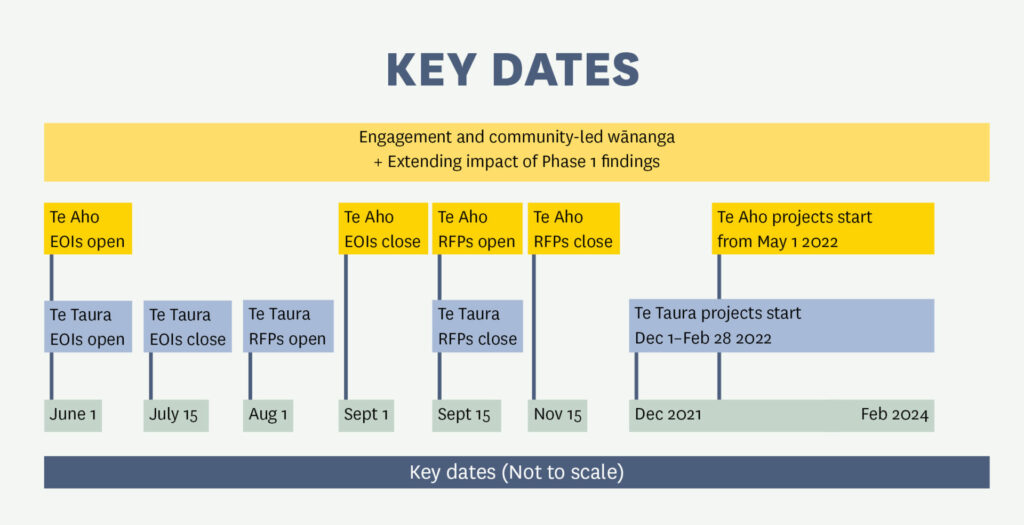

Are the project start and end dates strict?

The end dates for these projects are strict, yes. The Deep South Challenge is only funded until June 2024. All research projects must be finished by February 2024, in order to ensure we can do the best post-project engagement possible. The long timeframes for assessing and contracting projects reflect our experience in how long it can take to contract with multiple partners, and also take into account delays in research. But these timeframes are not targets – if there are no problems with contracting, projects can begin as soon as they are ready.

Do I need to know the exact cost of the project for the EoI?

For the EoI we only ask you to give us an indication of the total project cost. The full breakdown and detail of the project budgets will be worked through in the full RfP and we will provide you with detailed guidance notes to support you to create a detailed budget that meets the needs of your project.

Is there a minimum time-frame for projects?

A key part of our funding decisions will be ensuring that the timeline and budget you propose is suitable for the scope and nature of the project. We would expect projects to take anywhere between six to 18 months, but we will provide more detailed guidance during the RfP process.

Can we get funding to create a final product, like a book, a handbook, a documentary or a board game?

Our research funding supports knowledge gathering and knowledge generation. A product, such as a book, may well be a vital output from the research, and a natural response to your research findings. You can allocate some of your budget to supporting these kinds of outputs. We want your research to be useful and usable, both for your own community and for other communities. Please do keep in mind, however, that the research itself is the main game.

Can non-Māori researchers apply?

As this funding is for the benefit of Māori communities, we expect Māori research teams and/or Māori communities to be leading and driving research projects. Some teams may include Pākehā or tauiwi researchers who bring specific expertise, but this fund is to support research that is by Māori, for Māori.

We would like some specific expertise/science input into our project, but we’re not sure who to approach, can you help?

In developing your EoI you can identify areas where you might want some external support or a specific set of skills. We may be able to help connect you with scientists or other expertise to help you with your project.

Are scholarships available?

We encourage projects to consider the opportunities for growing the next generation of researchers. There is scholarship funding available and we will discuss the process for distribution of scholarships with project teams. At this stage, please indicate on your EoI if you have a potential scholarship student within your project, or would like to support one.

Kaupapa specific: Will you fund projects that focus on…

- Climate adaptation strategies

- Pest control

- Health

- Our marine area

All these projects are in scope, but the focus of the activities must have research and climate change at the centre of the project. By “research,” we are referring to the processes of knowledge/mātauranga creation, application and/or transmission. In terms of climate change, we are taking a broad approach, i.e. climate justice, resilience relationality with te taiao. That could include kaupapa that are not specifically ‘climate focused’ but are important interventions to climate impacts. As above, the output (such as a climate change strategy) is a response to the research findings, rather than the primary focus itself.

How important is it for us to partner or collaborate with other groups or organisations? Is the kāhui able to suggest or recommend potential partners (and/or make introductions) if we don’t already have any?

There is no requirement to partner with anyone else, but for many projects it will make sense to work collaboratively, or to utilise/access data or expertise that is held with others (for example, local or regional councils). If you don’t already have research partners lined up, but have an idea of what your needs might be, we may be able to identify potential researchers or existing data that could support your project. Please ask if so! It will depend on your kaupapa, so we encourage you to get in touch with our engagement team early.

Is specific climate language required in the EOI?

E Kao! The first part of this process should feel like a conversation or dialogue, so we encourage plain language applications that get to the heart of your project – i.e. why the research/rangahau is needed, what the project will involve, and how it will benefit or impact the community or people you are working with/on behalf of. You do need to demonstrate that your project is responding to a need/gap/opportunity in relation to the causes or impacts of climate change (in fact, this is key to presenting a strong proposal). But! we acknowledge that a genuine mātauranga Māori approach does not treat “climate change” as an isolated environmental issue. Strong EOIs will clearly articulate the connection between your project goals and outcomes, and the causes and impacts of climate change, whether they be environmental, physical, cultural, spiritual, social, political, legislative, health, justice etc etc. And don’t forget that you can submit your application in te reo Māori!

Do we need to have “qualified” researchers involved in our project?

Not everyone who applies will be immersed in formal academic research landscapes, and we recognise that mātauranga is held by kaumātua and haukāinga, whose knowledge and research experience is embedded in (and springs from) a physical place as opposed to an institution. We do, however, encourage you to think about how your project may build on or connect with other relevant research that may already exist in relation to your kaupapa. This will be one of the areas explored during the RFP stage. If you are unsure of what research might exist in your area feel free to reach out. You can also look at our website to see the kinds of projects that have been funded in the past.

Does the funding have more of a community focus, or is it of equal value to work with Māori Trusts/Incorporations etc?

The funding is intended to support research projects that are clearly able to link the issues and outcomes for a given group (whether that be a whānau, community, trust, or incorporation).. The research should have an impact on that group and we encourage you to look at the assessment criteria (on this page) for more detail around assessment.

You have asked for early applications so that the kāhui can ask pātai of the research if needed. Is it advantageous to put in an early EOI before all the research partnerships are in place, or wait until closer to the deadline when the research has been better finalised with partners?

We do encourage early applications if you feel your project proposal is established and ready. We will only get in touch with you if we think your EOI would benefit from additional information, or if something is unclear. If you already know that you have gaps, it would pay to wait to submit an EOI until you have as much information as possible.

Are there particular things the funding can’t be spent on?

We will be releasing a more detailed guide to help you formulate the detail of your budget (including exclusions) prior to the RFP deadline.

Do you anticipate heavy subscription to the fund? What is the total funding pool and number of applications you are looking to fund?

Our total pool of available funding is $1.4m and we do expect to receive a high number of EOIs. However, each project will be assessed on its own merits, and there is no cap on the number of projects we are able to fund, only on the total pool itself.