New research preparing rangatahi for an uncertain climate future

- AUTHORMeriana Johnsen

- Tuesday, March 1, 2022

New research preparing rangatahi for an uncertain climate future

Māori and Pasifika rangatahi will be among the most impacted by climate change. This project, funded through Living with Uncertainty is set to grow their capability to lead communities in an uncertain, climate change impacted future.

It comes as the IPCC releases the Working Group II report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, highlighting how climate change will impact communities both physically and socio-economically, and ways in which people can adapt to these impacts.

Reshaping communities: how and where we live, how we use our land, and how we work, is at the heart of The Deep South Challenge’s latest funding round, Living With Uncertainty.

Before covid-19 hit our shores, bringing forth the now well-known adage of “living with uncertainty”, researchers were invited to put forward proposals for projects that would help prepare communities, iwi-Māori, policy-makers and decision-makers to live with the uncertainty of climate change.

Mana Rangatahi: Climate change decision-making is one of three new climate adaptation projects which will work with Māori and Pasifika rangatahi aged 10 – 14 from two different Canterbury schools at high-risk of flooding.

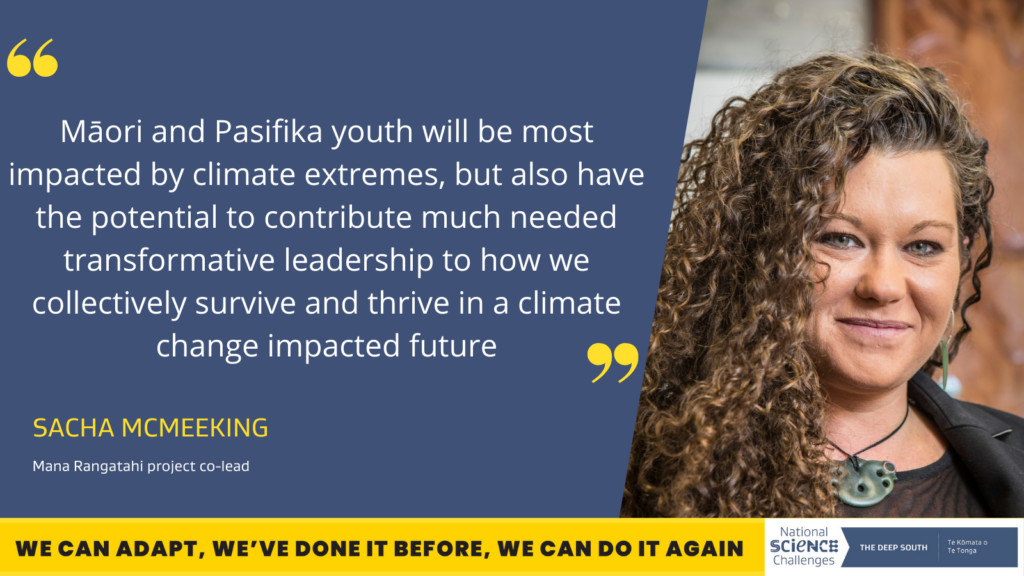

It is led by Canterbury University professors, Bronwyn Hayward (a coordinating lead author of Chapter 6 of the IPCC report), Executive Director Māori, Pacific and Equity Sacha McMeeking (Ngāi Tahu) and Distinguished Professor and Director of Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies, Steven Ratuva.

The project will work with rangatahi to design pathways to navigate the climate future, by drawing on their cultural narratives and values to conceptualise how they will respond to climate scenarios.

“Māori and Pasifika youth will be most impacted by climate extremes, but also have the potential to contribute much needed transformative leadership to how we collectively survive and thrive in a climate change impacted future,” McMeeking says.

A number of climate hui/talanoa/tala will be hosted with rangatahi and their whānau to consider future climate scenarios and how they might redesign their communities in the face of these.

Professor Ratuva, Director of the Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies says it is important climate adaptation focuses on whānau and communities, rather than individuals, Ratuva says.

“The consequences of one’s action impacts on others so addressing the climate crisis is a collective responsibility.”

Professor Bronwyn Hayward says she is excited to be supporting a project which is inspired by the power of ‘intergenerational learning’.

Other projects funded through the Living With Uncertainty round include: Simplifying real options analysis for climate change adaptation, which will create a tool for councils to more simply appraise the likes of roading improvements and sea walls; and Supporting community wellbeing when water is scarce, looking at the effectiveness of measures to protect water security.

The strength of indigenous values in guiding communities and businesses in the face of climate change is a major finding of a recently published paper on culture and climate change, authored by Priya Kurian, Debashi Munshi, Sandy Morrison, Raven Cretney and Lyn Kathlene. This paper features in the IPCC Working Group II report.

Conducted prior to the pandemic, it uses tourism as a case study of how cultural politics is influencing climate adaptation.

It found over half of tourism businesses were extremely concerned about climate change. While there was some awareness of its major impacts such as shrinking glaciers and rising sea levels, there was ultimately a lack of urgency in the sector for dealing with large-scale disruption in the near future.

Where adaptation approaches had been adopted, they tended to be carbon-intensive solutions like using helicopters to reach glaciers and generating artificial snow on ski-fields.

Māori tourism businesses were found to have a greater awareness of climate change impacts, because of their intimate relationship with the natural environment.

“I think tourism is about storytelling and introducing those stories relevant to Te Āo Māori, and Papa and Rangi is one way in which you can educate people about the environment and kaitiakitanga,” a Waitomo Caves guide interviewed for the research said.

The values of kaitiakitanga (guardianship of nature) and whānaungatanga (relationships and connections between people, communities and all living things) were found to provide a possible pathway for not only tourism businesses but at a political level to guide more sustainable practices into the future.

A concerted political push was needed, with a national climate adaptation plan with clear guidelines for tourism businesses, was needed to future-proof the sector against climate impacts, the report concludes.

STORYTELLING

FOR CHANGE

The Deep South Challenge has always experimented with supporting or initiating different kinds of storytelling to drive climate adaptation. These long-form magazine features allow us to weave different research projects into new patterns, helping us to see our research in different ways.