- AUTHORChange is nothing new in Te Hiku o te Ika

- July 16 2019

Change is nothing new in Te Hiku o te Ika

The iwi of Te Hiku o Te Ika are concerned about the impact of climate change on household drinking water. Results from this research, grounded in three rural Northland communities, have now been published in MAI: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship.

Isolation in the Far North means that roof-fed tank systems are the predominant source of drinking water for these communities. Understanding how climate change will impact water supplies has helped these communities prepare for the future, prioritise actions and mitigate detrimental effects.

The large research team led by Wendy Henwood of Te Rarawa included mana whenua community researchers at each location, iwi members, the Whāriki Research Group (Massey University), ESR and NIWA. Community researchers recorded daily rainfall and temperature data, surveyed household drinking water infrastructure and monitored water quality by taking household samples. NIWA and ESR team members used the data to model climate change scenarios and E.Coli contaminations, and kaumatua contributed mana whenua views.

The project highlighted the potential impacts of the general “hotter, drier” climate predictions for Te Hiku on the security and safety of drinking water supplies. Overall lower rainfall suggested the need for greater tank storage volumes. However, increased ambient temperatures are likely to converge with longer storage periods, to increase the pathogen count in these drinking water stores.

Throughout the research, practical strategies and innovations were shared about how to minimise water contamination, including about where to place septic tanks, how to protect water sources, the need for possum and rat trapping programmes, the importance of regular maintenance and upgrades, and de-sludging tanks. First flush diverters, UV treatment, and filters were described as solutions to improve water quality in some situations. Communities were acutely aware of the need to store more water and this, as well as the need for infrastructure upgrades at a number of households, all involve cost.

While the research focused on household drinking water, the issue was not viewed in isolation. Water is part of the environment, the people, and a whakapapa to Ranginui and Papatūānuku. Fresh and salt-water are the basis for land-use decisions (farming, gardens, orchards, fishing). Lifestyles revolved and revolve around its catchment. By creating specific, located, Māori knowledge about water sustainability, as a key dimension of community viability, this project has kick-started preparations in Te Hiku for the effects of climate change on people, ecosystems, lands and economy.

Quotes from kaumātua are woven throughout the final research report (see below) and are a moving testimony to the wealth of mātauranga Māori held in Te Hiku about our changing climate.

Local kaumatua have always observed and lived by the weather, practised kaitiakitanga, and acknowledged water’s vital interconnectedness with the environment. These elders are not fazed by the impact of climate change. Their resilience stems from a lifetime of working with the weather, growing up valuing water, and having the necessary knowledge and life skills to adapt to changing situations and realities. Theirs is an attitude that broader New Zealand could learn much from.

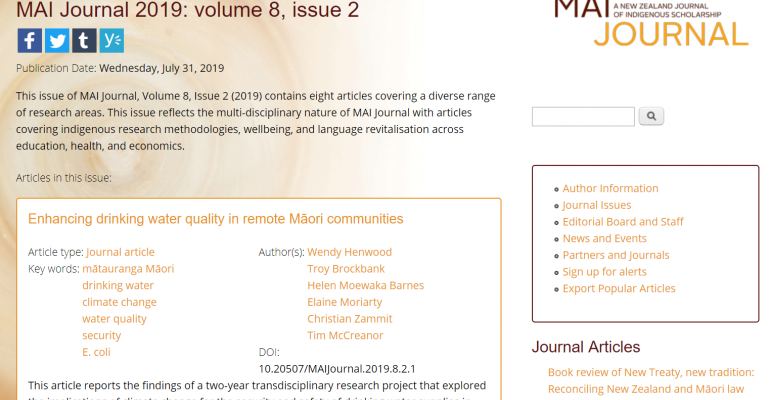

An article on the research, Enhancing drinking water quality in remote Māori communities, has just been published in MAI Journal. Read the final research report here.