- AUTHORWorking backwards to prepare for climate change

- March 24 2020

Working backwards to prepare for climate change

New research released by the Deep South Challenge: Changing with our Climate supports decision-makers to map out how decisions can be made now for ongoing climate change impacts, by starting with the future we wish to avoid. The research report, Supporting decision making through adaptive tools: Practice Guidance on signals and triggers, has been a multi-disciplinary and multi-institute effort, with team members from Victoria University of Wellington, Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research, and NIWA.

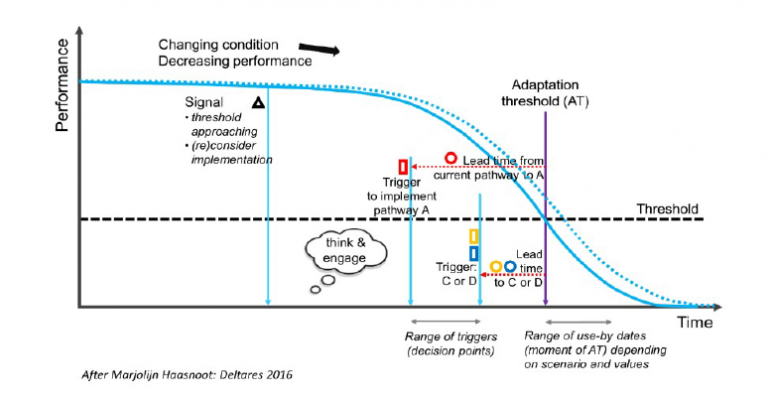

Led by Judy Lawrence (Victoria University of Wellington), the research undertaken over the last two years alongside practitioners, encourages decision makers to understand how to stage decisions, by identifying “adaptation thresholds” (the future situations we want to avoid), “triggers” (identified moments at which we action a given decision), and “signals” (very early warning bells, that tell us things are beginning to change).

The team’s report is presented as “practice guidance” and complements the existing MfE Coastal Hazards and Climate Change Guidance (2017). These form key tools and processes in the planning toolbox for councils, and for river and coastal hazard managers, looking ahead to a future of sea-level rise, extreme storms, and changing rainfall patterns.

“We want to support local capability and capacity for adaptation planning,” says Dr Judy Lawrence, “for changes to climate that will undoubtedly impact where we live and and how we go about our business, as well as how we protect public safety, health and well-being.”

The research presents various methodologies for identifying and tracking signals and triggers. One case study, led by Scott Stephens at NIWA, demonstrates how to identify credible and relevant signals and triggers for coastal flooding, with a monitoring period closely aligned to local government planning mechanisms. A second case study led by Daniel Collins (NIWA), looks at riverine flooding, and explains, for example, the importance of understanding whether chosen signals and triggers successfully warn of an approaching adaptation threshold and give sufficient time to act, while not giving false alarms.

The authors also discuss case studies on both the Hutt and Lower Whanganui Rivers with evidence about common barriers that can slow the uptake of Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning across the country. Finally, Nick Cradock-Henry from Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research uses scenarios to stress test the signals and triggers for different future conditions for their relevance, credibility and legitimacy. Paula Blackett from NIWA designed the processes for developing the signals and triggers.

All examples point to the importance of integrating local knowledge and local interests, as well as social, cultural, economic and environmental conditions into the design of signals and triggers.

This research complements existing Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning resources. The report authors are clear that for this kind of planning different kinds of technical expertise are required based in science, policy and the practice of engagement.