Ko te kawa o te ora

- AUTHORKo te kawa o te ora

- February 1, 2021

Ko te kawa o te ora

Kai-karanga: Erina Henare-Aperahama

Kai-karakia: Ruia Aperahama

Karanga

E Rangi e Papa whakarongo mai koia ki tēnei karanga o te wā nei eeeeeeiii

Tūrou Hawaiki ki te kaupapa o te wā nei eeeee

Mate i te mate i te pā hana hana o wai ori ake nei eeeeei

Nau mai oro mai ki tēnei marae tapu o te aotūroa nei eeeei

Sky father, earth mother, please listen to the call of our time

May the power and virtue of Hawaiki be upon us all

From death to death, a swaying wave of life

Come, resonate here in this sacred courtyard of all life

Karakia, Tauparapara

Ko te kawa o te ora, ko te kawa o te ora,

Ko te kawa o te ora, tēnei ka tākina,

Ko te kawa o te ora, tēnei ka hikina

Eeei Tapu Tapu mai koia ko Rangi e tū nei

Tapu Tapu mai koia ko Papa e takoto nei

Tapu tapu mai koia ko tēnei mana

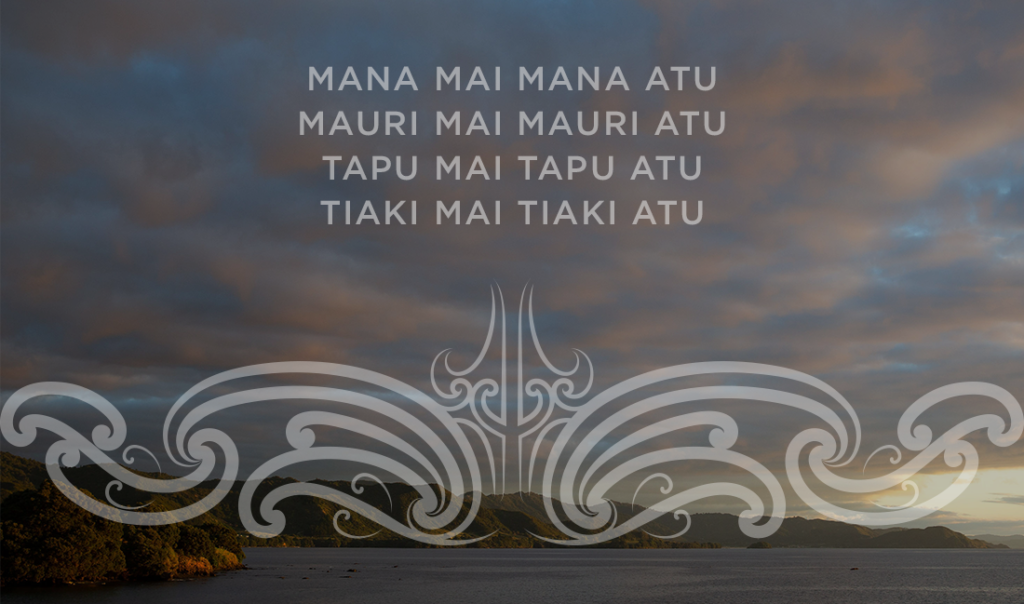

Mana mai, mana atu

Mauri mai, mauri atu

Tapu mai, tapu atu

Tiaki mai, tiaki atu

Haumie e hui e tāiki e!

The cycle of life, the cycle of life

the cycle of life recited

the cycle of life lifted up

Sacred indeed is Sky father

Sacred indeed is Earth mother

Sacred indeed is this power

This power outward, inward

This outward essence, this inward essence

This sacredness inward, outward

This protection inward, outward

Alliance, consensus

Together one and all

This karanga and tauparapara were composed in late 2020 for the Deep South Challenge by Matua Ruia Aperahama, member of our Kāhui Māori, and an extraordinary musician and educator.

This story takes you through the values and the narrative that underpins our website. It emerges from workshops with our Kāhui Māori and other kaupapa Māori researchers.

A whakataukī to guide our storytelling

Emerging out of the kōrero of the Kāhui Māori, Ruia Aperahama proposed this whakataukī as a galvinising force for our storytelling.

Reciprocity underpins and surrounds this whakataukī. In order to change with our changing climate, we need to recognise and integrate reciprocity into all aspects of our work.

Rather than recalling the pūrakau of particular hapū or iwi, it’s open and general enough to allow a way in for many audiences.

Whaea Sandy Morrison, our Vision Mātauranga programme lead, also noted the reciprocity embedded in Pacific cultures (for example, through tributes and blessings), recalling Aotearoa’s obligations to Pacific nations under threat from climate change, and drawing a geographical link in our research from the Pacific region to the Southern Ocean: across time, space and scientific disciplines.

This reciprocity can nurture – grow – our sense of authority and agency to make decisions. It cultivates vibrancy, enhancing our health and well-being. It generates a reverence for each other and the natural world, and provides us with a strong understanding of the cultural and physical limitations we must work within.

This reciprocity can also activate an ethic of energetic care, for each other and our environment. Rather than allowing panic or fear to lead us, we can move forward with agency and hope.

How did we interpret this whakataukī in visual design?

We wanted to find a way for our non-Māori audiences to experience a shift in perspective. This shift might be in an understanding of physical or social hierarchy; to a sense of time or place; or in the way we perceive the nature of “authority”.

Equally, we intended that our website would enable our Māori audiences to feel a sense of recognition for their everyday realities.

We want our online presence to reflect (as well as we can), indigenous ways of being and relating, to each other and to our natural world.

We contacted the talented crew at Āriki Creative and asked them to create some kōwhaiwhai based on this whakataukī and the themes we developed (below).

We hope our website is inclusive of all audiences. We hope to provide some ways to activate our collective agency. We all need to seek the hope, mana and confidence to start making decisions.

Themes

- Ahikāroa | place, belonging, connection

- Mana | agency, authority, working with our strengths

- Taputanga and Atuatanga | reverence, protocols, limitations

- Kaitiakitanga | rangatiratanga, ki mua ki muri, intergenerational responsibility

- Ātea | navigating, journeying, from the Pacific to the Southern Ocean

Ahikāroa | place, belonging, maintaining connection

We acknowledge the primacy of place and of belonging in all climate adaptation work.

We recognise mana whenua, at the same time as being careful not to homogenise hapū or iwi Māori. Our narrative acknowledges the multiple claims of mana whenua, as well as multiple knowledges, rather than suggesting that any single source of knowledge or power will deliver robust solutions.

Climate change – like other historical upheaval – is likely to separate at least some of us from our homes and whenua. Decision making is especially traumatic when we risk being separated from places where we hold ahikāroa. Adaptation solutions must strengthen the decision-making powers of local people, particularly ahikā.

Ahikā are already observing local environmental changes – to water sources, environmental indicators in flora and fauna, and to patterns in weather and climate.

If we all learn how climate change may impact our local food sources, fishing grounds, rivers and forests, habitable land and recreation spaces, we can find robust local solutions.

If we spend time understanding the values that drive our decisions, we are also more likely to find collaborative, robust adaptation solutions and opportunities.

Mana | agency, authority, working with our strengths

Our research speaks directly to decision makers. We are all decision makers, regardless of how small or large our sphere of influence.

We respond to and support decision makers – on marae, in the community, around boardroom tables, and in local and central government – to work out what we can do now, and to start to do it. Our research supports decision makers to understand a wide range of climate risks and to plan to deal with those risks, over the short and long terms.

There is an urgency to act. But to overcome the real barrier of despair in the face of massive uncertainty, we meet our audiences with positive, action-focussed and even light-hearted language.

Te mauri, te mana, te ihi, te wehi. These are both precious and volatile.

In order to embrace their own agency and to collaborate, decision makers need to feel seen, heard, respected and honoured. Te mauri, te mana, te ihi, te wehi. These are both precious and volatile.

We communicate hope and activate agency by providing ‘glimpses’ of success – examples where others have faced near-impossible climate-related challenges and found a way through.

We provide clear signposts for users to find their own pathways towards their own solutions. We are clear about who is responsible for particular adaptation barriers.

We have hope and believe we are all capable of change. Our kaumatua and our ancestors survived great change. ‘The thing is not to panic’.

Tapu, atuatanga | reverence, protocols, limitations

Climate change will likely disrupt wāhi tapu, taonga Māori and whakapapa Māori. We acknowledge the immensity of the hara, the wrong that will be caused to tangata whenua if we choose not to act.

Whatever names we know them by, atua are speaking to all of us. They speak through the rain, the sun, the tides, the clouds and the wind. Immense change is upon us, even if the rate of change is uncertain.

We acknowledge that Western science – especially climate science – must connect with a sense of reverence for the natural world. Both wairuatanga and whakapapa help us understand how the human and non-human worlds are related. If we feel pain when damage is done to the natural world, we will be more likely to respond. Rather than setting out to dominate or control nature, our research supports solutions that work with nature.

The sky is filled with grief. Over the southern horizon, the ocean is losing patience. It can only absorb so much poison. It melts and swells, and sends us small and large messages. Native species flower earlier. Fish migrate further south. Shellfish don’t grow as large or as strong. Frost arrives late or not at all. Atua make themselves known in the form of giant storms and massive tides. We know the damage we have caused. We know our ancestors are changing. We know we have to figure out how to change with them.

Ruia for example referenced Te Tai o Ruatapu and Parawhenuamea, as controllers of or personifications of destructive tides, tsunamis, floods. We hold these stories and others close, even as we’re careful not to overstep hapū control of their own pūrakau.

Kia mau te taura o tēnei o ō tātau waka, koi motu ka haria e Parawhenua mea ki runga ki te tūāhu o tāna tama (TJ 10/5/1898:7). / Hold on to the rope of our canoe lest it is severed and taken by Tsunami onto the sacred place of rituals of her son.

Ruatapu, son of Uenuku, convinced the gods of the tides to destroy the land and its inhabitants.

We recognise the importance of protocol in supporting successful adaptation. Protocols help guide our behaviour, and tell us what is permitted and what is restricted. By following protocol, we strengthen our relationship with and respect for our ancestors, and understand the challenges they faced and how they navigated change. We seek consensus and we prepare properly, which empowers us to act and keeps us safe.

Kaitiakitanga | rangatiratanga, ki mua ki muri, intergenerational responsibility

Climate adaptation is an intergenerational issue. The cause of climate change begins long ago, with industrialisation, colonialism and imperialism. If we don’t begin to change, those who will suffer most from climate change will be our mokopuna, and their mokopuna. We hold their lives in our hands.

We need to look in all directions, ki mua ki muri, ki runga ki raro, ki waho ki roto, to understand our guardianship responsibilities. We must also consider that guardianship without rangatiratanga – decision-making power – is an empty concept.

Our communities must be involved in making decisions about their own well-being, and about the well-being of our environment. Decision-making at all levels of society – especially and including in research – must be transparent and accountable to the communities it is supposed to serve.

Ātea | navigating, journeying, from the Pacific to the Southern Ocean

Sandy Morrison’s research, which begins at the beginning, in the wide open ātea of the Southern Ocean, opens with this karakia:

Te ao o te tonga, e whariki mai ra e

Nā runga I ngā hiwi

Ngā Pari-huka e, te ika-tawira,

Ka whakapou nei ōu, i.

The atmosphere of the south, stretching out wide

Above the mountain ranges

Beyond icy cliffs, where ancient fish flourish

And wonders, to which I humbly bow.

While no single iwi claims mana whenua over Antarctica, Polynesians were the first to navigate the Southern Ocean. We look to the Pou Whakairo of James York Robinson, opened by our board member Tā Mark Solomon in Antarctica, to understand the origins and purposes of ocean voyaging and ocean navigation.

Sometimes, change is necessary. Always, change requires great courage and even greater teamwork. Change can be exciting, adventurous and create new opportunities.

We are not afraid of change, because in the past, change has led us to new beginnings. Our ancestors have journeyed towards new knowledges and sources of culture, as well as in search of shelter and new sources of food.

The Polynesian navigator Hui te Rangiora travelled (some say as a giant reptile) to the Southern Ocean (resting half-way at the mouth of the Riuwaka River in Motueka).

Children perform haka like Pītotori to remember and honour him. Sandy tells, “This haka is well known to Tainui… It is synonymous with waka, navigation and seafaring. Its author is unknown as is the time in which it was recorded. It tells the story of a supernatural being called Hui Te Rangiora with a needle-like structure on its back which pierced the sky. When asleep, this taniwha resembles the silhouette of mountain ranges.”

Ocean navigation provides rich metaphors for the challenges ahead in climate adaptation. Sandy Morrison’s research project “Te Tai Uka a Pia“, due for imminent release, provides a rich source of material for navigation messages and imagery.

As our ancestors prepared to leave their homelands and travel in search of new territory, so must we consider the compromises, and the opportunities, ahead of us as our climate changes.

STORYTELLING

FOR CHANGE

The Deep South Challenge has always experimented with supporting or initiating different kinds of storytelling to drive climate adaptation. These long-form magazine features allow us to weave different research projects into new patterns, helping us to see our research in different ways.