- AUTHORNew Zealand wine - an industry under stress

- Wednesday, June 26, 2024

New Zealand wine – an industry under stress

Winemaking is about balance, but climate change is already impacting the conditions under which growers can be confident about the quality of their grapes. Higher temperatures, less rainfall, new pests and disease and changes in water demand and supply create challenges for growers and wine makers. Although we know more and more about what sort of conditions we are likely to experience in the future, for some primary industries – like wine making and grape growing – climate change is going to happen alongside other shocks (like rising input costs), or stresses (like less water). Like any climate change adaptation story in Aotearoa New Zealand’s vitally important primary sector, the one around climate, water and wine is complex. But, ultimately, the pressures are clear – so what’s the right way to respond?

New Zealand is the world’s sixth largest exporter of wine, growing by nearly 25% between 2022 and 2023, to a record $2.4 billion. And it’s an industry under stress. This project looked at a range of issues coming together under changing climate conditions to add to our viticulture growing pains, and considered these in the context of other external pressures common across the primary industries, that have had our food producers adapting in one way or another for some time.

Drivers of change

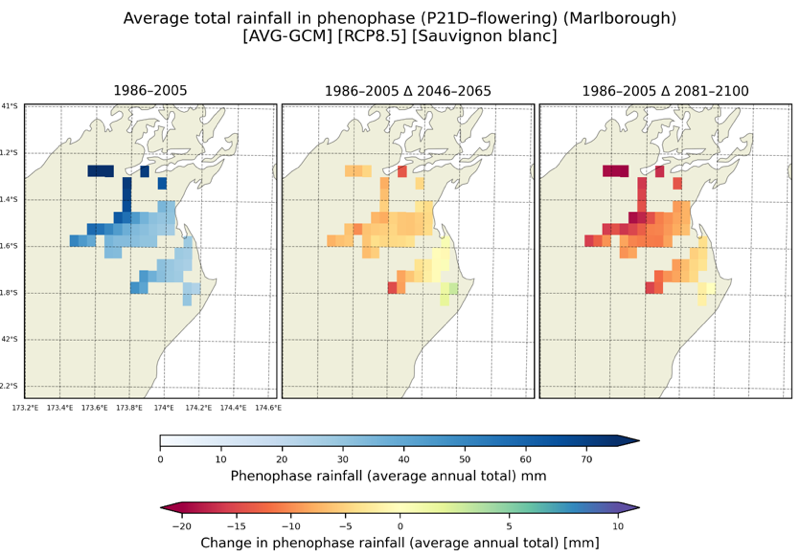

The Marlborough wine region is located at the top of the South Island. It is the country’s best known and largest wine producing region. The area is characterised by a range of topography and aspect within its many valleys which combined with young and diverse soils and subsoils creates micro-variations across the region. Glacial advance and retreat over two millennia has resulted in a complex, terraced landscape comprised of river flats with free-draining alluvial soils, and clay and loam hillsides. It is a maritime climate with high sunshine hours, typically dry conditions – particularly during harvest (February-April) and protected from cold southerlies by mountain ranges to the south, providing ideal wine growing conditions. There are over 30,000ha of vines in Marlborough (around 2/3 of the national total), making it the country’s largest wine region. Much of the region is dominated by a single varietal (Sauvignon blanc), which accounts for 72% of New Zealand’s overall wine production — and 86% of what we export to the rest of the world.

Marlborough is one of the sunniest and driest regions in New Zealand, but is also prone to earthquakes – with four major tectonic faults (Hope, Clarence, Wairau, and Awatere. Following their recovery from an earthquake in 2016, growers were interested in understanding future challenges. They recognised the need to adapt their practices to go on responding not only to known environmental and market pressure (labour, capital, infrastructure) but also new ones emerging as a result of changing rainfall, extreme weather and other impacts.

Many wine growers operate in small rural communities, where problems like housing and labour already compound to make things periodically difficult, but climate change is upping the ante.

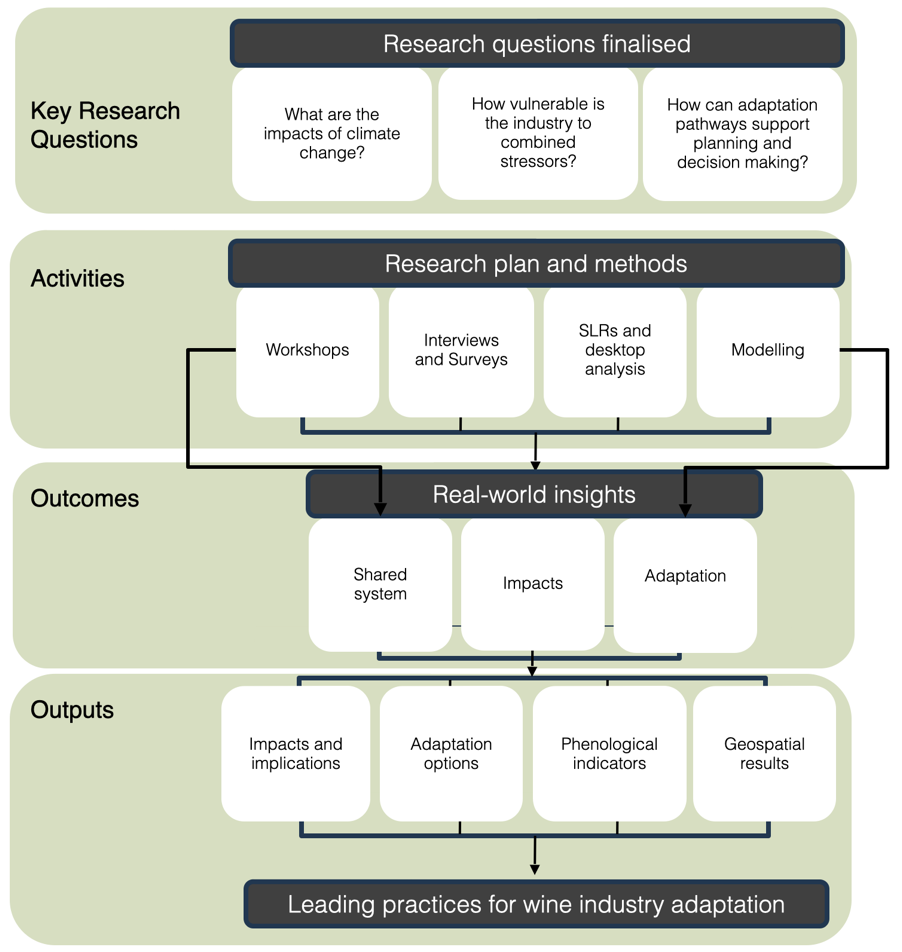

This project asked: how likely are the impacts of climate change? How vulnerable are growers to these stressors? And: how can we use adaptation pathways planning to identify impacts and take action?

The approach

Adaptation involves taking action to avoid, withstand or benefit from current and projected climate changes and their impacts. To support adaptation planning, therefore, it is necessary to understand what future conditions are likely to be and consider the range of actions or steps to be taken in response to those changes. To help think about about the climate and environmental issues facing wine growers in Aotearoa New Zealand, this project used a multi-method approach including workshops, participatory engagement, a comprehensive literature review, surveys and grape phenology modelling – that is, exploring the life-cycle of grapes in detail to establish how cycles are changing, where in those cycles grapes are vulnerable to different climate change impacts, and what that means for overall production.

The idea of the multi-method approach was to seek a shared understanding of the issues at play, as well as to build capability and capacity for response, and to develop a suite of opptions for organising and executing that response. The results of the discovery process included detailed geospatial modelling, development of phenological indicators, adaptation opptions, and reporting on climate impacts and the implications of those.

What did we find?

Climate change is expected to result in warmer and drier conditions for Marlborough. When it does rain – it is likely to be more intense, which may lead to flooding and damage to critical infastructure. The wine industry will need to adapt to reduce climate risks and realise opportunities.

Like so many complex primary production systems, amassing information on impacts and implications of climate change gets messy very fast. The contant focus of this project had to be about wanting to help, so it was critical that findings would help with broad understanding, build a reliable and usable information base and help growers with planning. Ultimately, growers need decision-relevant science and actionable information.

And they know it.

It was very clear that experience and awareness of extreme weather and other climate impacts was growing; the industry was already very focused on this. We asked about experiences of drought, water ponding, changing temperatures and a range of other climate change indicators that might alter growing seasons or change the nature of the grapes – which in turn can have a massive impact on how a wine tastes. Over 70% of surveyed growers said both summer and winter temperatures had increased. More than half said the growing season had decreased. We tested this in Marlborough, as a focus area, but results across much of the country’s other wine-growing regions was similar.

It’s not only that we need the water consistently, [it’s also] the timing of needing the water. It’s also the availability of the water and future regulation. You just can’t bank on it anymore.

– Wine grower, Marlborough

One of the key issues for growers was water – this was on the mind of many we talked to or had input from. Many people referenced a significant drought event in 2019 and were able to talk about how reliability around wanter was changing; allocation, demand and predictability of supply had growers worrying about the future.

What does this all mean for wine?

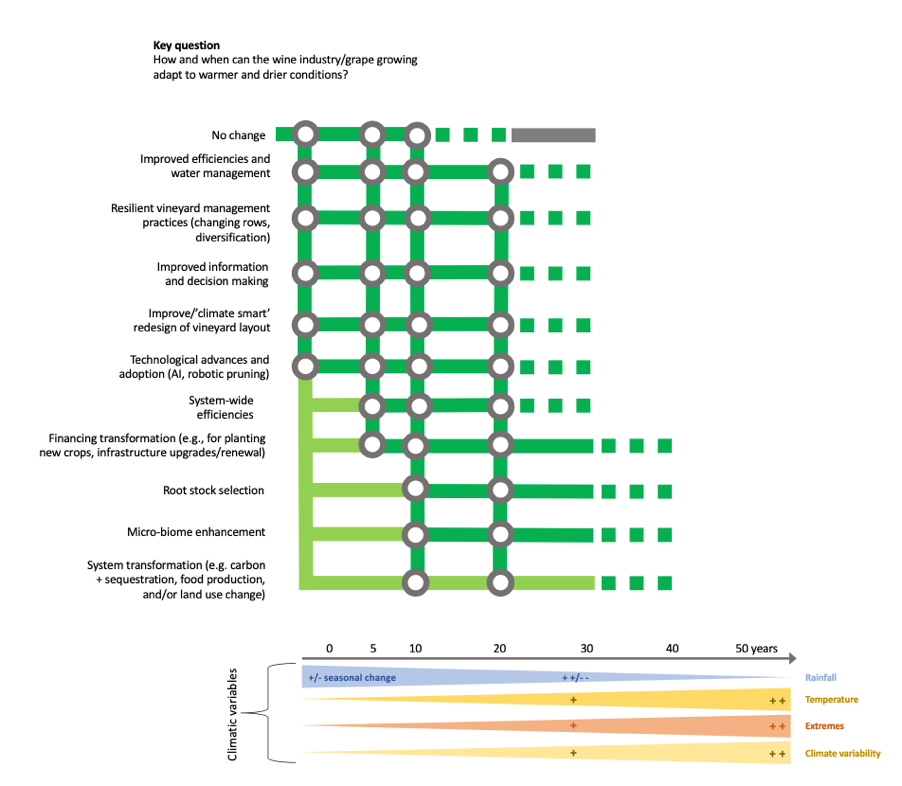

To support adaptation planning, stakeholders identified a number of different adaptation options to ensure the long-term sustainability of wine making and grape growing in Marlborough. By involving stakeholders in the planning process, new ideas were generated, links between options were explored, and the ways in which actions might

be implemented were discussed.

This shows the emerging adaptation adaptation pathway for grape growing and wine making in Marlborough. It is based on stakeholders’ input and illustrates the decisions and actions that could be used to support adaptation. Implementing the pathway will require greater coordination between individual growers and wine makers, as well as local and regional councils, iwi, communities, and other primary industries.

The horizontal axis of the pathway shows both a timescale and expected changes. The range of adaptation options considered are listed on the left-hand side of the pathway. Against each option is a combination of dots and lines. ‘Decision points’ are indicated by a circle, showing the point in time at which a decision needs to be made between different options relative to the x-axis. This is based on the premise that as climate changes some options will become less suitable as adaptation measures and so new ones may be

required.

The dark green lines show the time period over which an option can usefully address the priority in question, while the light green lines indicate options for which some preparation may be required.

We know that vines are more likely to grow under stressful conditions as the climate changes – and we know that this influences grape quality and yield. Unlike with other primary industries, like the dairy industry for example, there is much more sensitivity to the overall quality of the product.

Dairy is a volume commodity, whereas high value horiculture has a huge quality aspect – sugars, acidity, aroma – these are things that are impacted by changing climate, especially rainfall.

In another example, as we get more warm weather, we get earlier harvests and it yields grapes with more sugar but low acidity. Too late a harvest, and the opposite problem occurrs. “Harvest compression” means that as well as changes in the grapes themselves, growers are also competing for storage capacity and labour capacity – pressure comes on all these aspects of the system as a result of the shifting season.

These are all things that are impacting the reliability of the product. With a delicate product like wine, this is a serious concern for Aotearoa New Zealand’s reputation – not to mention the plight of individual growers who need to adapt.

All this is connected.

Adaptation must take into account systemic imapacts to generate a systemic response; but at this stage much of the thinking about climate change in viticulture is focused on the direct impacts of individual parts of the system – water, extreme weather, etc.

There is a real need in wine to close the gap between identification of the issues, understanding of the problems, decision-making and taking action to improve the long term prospects of the idustry. As always, incrementalism is the enemy of transformation, but as ever in primary sector adaptation, reality bites.